AMR – uniting the disciplines to understand behaviour and influence change

8 December 2020

4 mins to read

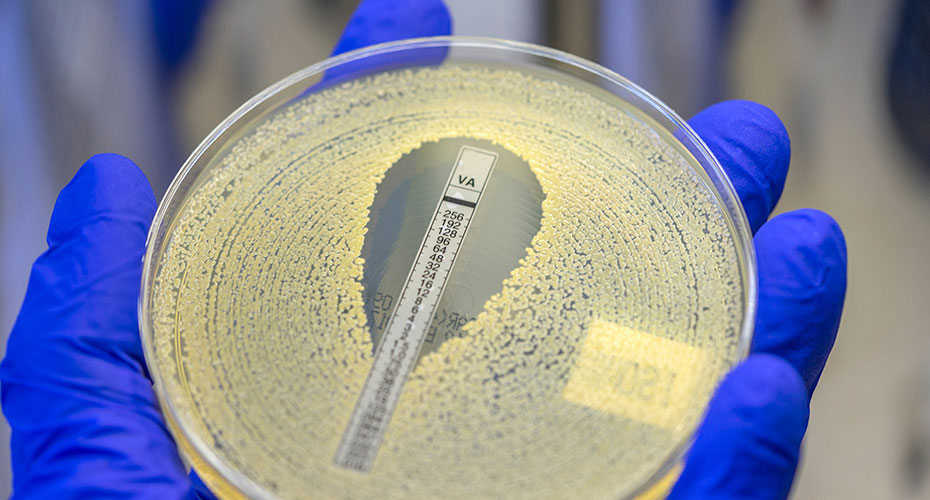

Studying cellular mechanisms and focussing on clinical use will only take us so far in the battle to reduce the impact of AMR. It’s also crucial to understand and influence behaviour across a broad range of interlinking, yet often disparate, global communities.

To achieve this, a truly interdisciplinary approach is needed. Exeter’s One Health ethos unites social scientists and specialists in humanities with microbiologists, mathematicians and many more, achieving a holistic approach to influencing policy and behaviours.

The key role of interdisciplinary working

Professor Judith Green, Director of the University of Exeter Wellcome Centre for Cultures and Environments of Health, said she was seeing an increasing recognition of the importance of the social sciences and humanities in global health issues.

“The big challenges of healthcare are no longer technological, they’re challenges of how our culture intersects with human, ecological and global systems. At a global scale, AMR is not just about individual decisions, but about the whole system. How did people come to think that antibiotics are a magic bullet, what’s the history of use in each area, what kind of relationships do people have with antibiotics? There’s an increasing understanding that you can’t just take one policy and apply it to different areas, without understanding local contexts. To overcome that, we need science, social science and humanities working together.”

Unpicking the economics of AMR

One strand of research at Exeter is working to understand and influence economic policy related to the development and use of antimicrobial drugs. Currently, a major global focus area involves regulating the use of badly needed new antibiotics, because over prescribing would hasten the emergence of resistance to the new drugs. Pricing is also an issue – most bacterial infections can be treated with inexpensive antibiotics and the drugs are prescribed within a limited treatment window. Consequently, antibiotics tend not to generate the requisite profits and returns for large pharmaceutical company R&D investment compared to drugs that treat chronic diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, depression or osteoporosis. As a result of this, many big pharma companies have stopped their antibiotic development work and much private sector R&D has transferred to the work of SMEs.

Dr Jehangir Cama is part of a collaboration looking at financial incentives to pharmaceutical companies to reinvigorate antimicrobial R&D. But the issues are even more complex. He said, “5.7 million people die annually in the world today because they can’t access existing antibiotics. So on the one hand, policy-makers have to consider measures such as higher pricing/reimbursements for new, innovative antimicrobials, to incentivise pharma to return to this field, while on the other hand you have people who are dying because they can’t afford the drugs – how do we solve this problem? Balancing these, along with incentivising the appropriate, controlled use of antimicrobials, is a very difficult policy challenge that requires global cooperation.”

Understanding the role of farming

The role of farming is a huge issue in AMR. Around a third of the antibiotic use in the world over the next 20 years is expected to be in China, in pork and chicken farming. In a country that is food insecure and has relatively little land for its vast population, joined-up working is desperately needed to find solutions.

To add to the complexity, in many parts of the world, little regulation exists in relation to antibiotic use in human or animal health. Companies that market antibiotics are often unscrupulous in relation to their role to limit use.

Seeking to further understand these complex intersections is Stephen Hinchliffe, a geographer interested in the social context of health and disease, particularly in relationship to food issues and environment.

“It’s going to be very difficult to feed the world without antibiotics, and it’s almost disrespectful to ask farmers to ‘behave better’, when they’re used to this infrastructure that antibiotics give them, without finding alternatives to improve animal health.”

For example, the Maasai Mara of Tanzania rely heavily on antibiotics to care for the drought-stressed cattle that are integral to their culture. “You can’t just go in there and say ‘please don’t use antibiotics because they’re harming the planet’”, Professor Hinchliffe explained. “You need to come up with alternatives.”

"It’s going to be very difficult to feed the world without antibiotics, and it’s almost disrespectful to ask farmers to ‘behave better’, when they’re used to this infrastructure that antibiotics give them, without finding alternatives to improve animal health."

Professor Steve Hinchliffe

Professor in Human Geography

AMR – the dark side of modernity

To put this on the agenda, the Exeter team compiled a WHO report on the cultural aspects of AMR globally, which argued that neglect of this issue was a major barrier to change. Professor Hinchliffe said: “So far there’s been a focus on behaviour, but we need to consider the cultural context, history, economic structures, the norms and expectation of a ‘quick fix’ of antibiotics, and then think about how that culture would have to change in the future to accept that science doesn’t always have the answer. We have to understand that AMR is part of the dark side of modernity.”

The issues often differ hugely between locations and communities. In Spain, the Exeter team reported that high levels of injury and sexually transmitted diseases after the Spanish Civil War led to General Franco ensuring penicillin was freely available, so people in the Catholic country did not have to admit to their priest why they needed medication. “The Spanish are used to buying antibiotics over the counter, like any supermarket product,” Professor Hinchliffe explained. “It takes time to change that culture of expectation.”

When research reveals paradox

Working towards change can also be complex. Among UK poultry farmers, antibiotics can be the first line of defence if a chicken falls sick. One recommendation to address this is pen-side tests, to establish if the infection would respond well to an antibiotic. Yet vets currently take a wide range of factors into account in deciding whether to prescribe antibiotics. Replacing this knowledge with technology could end up increasing the use of antibiotics, rather than reducing. “Sometimes you think you’ve got an easy technical solution, but if you lose those layers of knowledge, you can actually end up medicalising a problem and having the opposite effect than intended,” said Professor Hinchliffe. “We need to be really careful that we value the knowledge and practices of farmers and vets.”

Solutions to these issues can also stem from a better understanding of how farmers have adapted their practices to live with disease, rather than eradicating them. A tenth of the world’s population lives along the rivers that flow through Bangladesh, and producing fish is a benefit to rural development and of nutritional importance. However, water quality is low and disease levels are high, meaning reliance on antibiotics can be high. Here, Exeter research focuses on how farmers manage disease outbreaks, and the role played by each point in the system, from agricultural supply shops to the pressures applied by the pharmaceutical industry to buy products containing antibiotics.

Professor Hinchliffe said interdisciplinary working was essential to finding solutions. “In Bangladesh, our microbiologists realised that the health of a pond was dependant on the mixture of microbes in the pond, rather than the presence or absence of disease. Our contribution was to highlight the role of markets, and economic pressures in changing that microbial mix. Pressure on farmers can have a direct effect on the health or otherwise of the pond microbiome and the fish and other animals that are cultured in those ponds. That brings together the social with the microbiology – they both impact on each other. We have to think about them in a joined up way.

“At the moment, there’s too much focus on behaviour change, and we think the answer to that is education. But look at smoking – we all knew it was bad for us years before many people quit. We need to think about culture and legislation, and look for the right kinds of levers for change. A key area might be in the retail sector, and making sure that supermarkets, fast food and large restaurant chains globally can influence the ways our food is produced. That won’t come just by telling people antibiotics are bad for the world.”

Meet our researchers