Professor Ben Groom

Dragon Capital Chair in Biodiversity Economics, University of Exeter.

Dr Joseph Bull

Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, Canterbury, UK.

Sophus zu Ermgassen

Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology, Canterbury, UK.

UK government biodiversity funding: big gap between reality and rhetoric

UK government biodiversity funding

UK government biodiversity funding

UK government biodiversity funding

This article accompanies the following Correspondence in Nature.

The UK must match claims of global environmental leadership by reversing world-leading declines in biodiversity investment.

On the 18th May, the UK government announced the intention to introduce a legally-binding target to halt species losses by 20301, a world-leading national biodiversity commitment. This follows months after an ambitious pledge to protect ’30 by 30’ (30% of land by 20302), and the release of the influential Treasury-commissioned Dasgupta Review on the Economics of Biodiversity, which argues for systemic economic changes to address contemporary biodiversity declines3. Such commitments are potentially key signals of international environmental leadership, especially important given the UK government’s role as the hosts of this year’s pivotal COP26 summit in Glasgow4.

However, in the Queen’s speech in May, the government also committed to ensuring they can be ‘held accountable for making progress on environmental issues’5. A new dataset published in Nature Ecology and Evolution exposes a gap between the rhetoric and reality6. Not only has the UK government’s funding for biodiversity fallen in absolute terms since 2008 even on the backdrop of a growing economy7; the dataset reveals the UK’s public biodiversity funding as a proportion of GDP has not kept pace with other countries across economically emerging and wealthy economies alike whose public funding has steadily increased over the same period. The UK remains the twelfth most ecologically-degraded country globally, bottom of the G7 by a wide margin8. All this, despite that the World Bank ranks the UK is the world’s sixth richest economy, and that the UK economy has grown by 11% across the same time period. The resources to invest in nature, if the government so chooses, have never been more abundant.

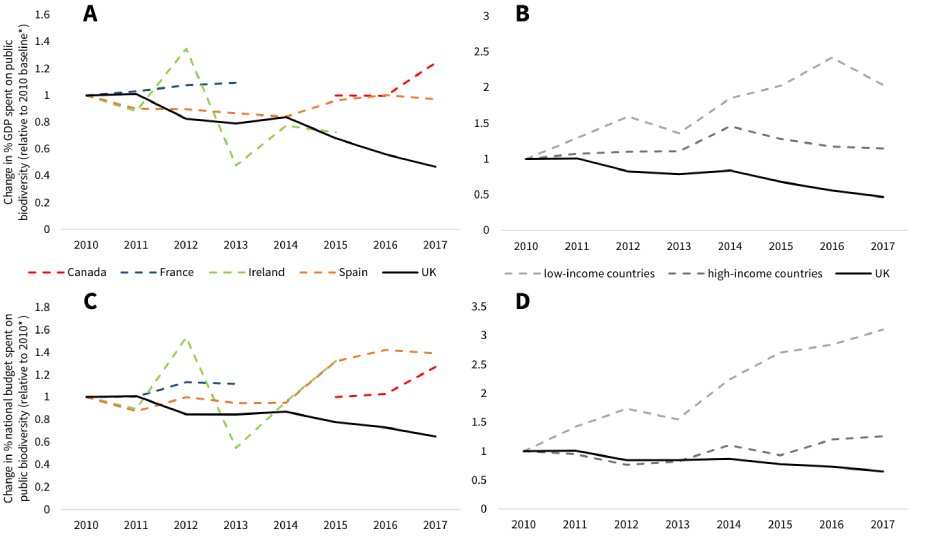

Seidl et al.’s work reports standardised time series of countries’ public sector biodiversity-related expenditure (e.g. spending on protected areas, agri-environment schemes) from 2008-20176. Their dataset contains the first estimates for national biodiversity expenditure for 26 countries through their participation in the UN’s BIOFIN biodiversity expenditure review, and government-reported data for a further 5 countries. The UK figures are based on government expenditure data reported by the Joint Nature Conservation Commission7. We requested and disaggregated Seidl et al.’s data by country to reveal stark trends – whilst the public biodiversity spending as a percentage of GDP reportedly rose by an estimated 104% across low-income countries and 15% across wealthy countries from 2010-2017 (we use 2010 as the baseline year as some countries changed accounting practices in the run-up to the 2010 COP), it fell by 30.5% across the same time period in the UK (Figure 1). If we include the government’s recent announcement to increase Natural England’s budget by 47%9, the UK’s spending on domestic biodiversity conservation is still approximately 20% lower than in 2008 in real terms; and this increase is partially undone by the UK government’s foreign aid cuts, some of which were invested in biodiversity conservation-related projects abroad.

Whilst a decline in biodiversity spending in absolute terms is consistent with the UK government’s austerity policy, the UK also stands out for the reduction in biodiversity spending as a percentage of its national budget - clearly demonstrating a deprioritisation of nature investment relative to other policy priorities, not just an absolute reduction. This stand-out decline persists when only comparing with other countries reporting official biodiversity expenditure statistics rather than BIOFIN survey results (Figure 1). Whilst the absolute values of national investments cannot be directly compared because of alternative accounting methods (time trends can be though as Seidl et al. standardised the data as far as possible over time), the data suggest that this is not because the UK’s funding is high in absolute terms – Seidl et al.’s data suggests the UK spent $510 million (2010 constant USD) on biodiversity in 2017, compared with $715 million (2010 constant USD) in Canada, and $2.23 billion in France (2010 constant USD, most recent datapoint 2013).

Figure 1:. Changes in biodiversity expenditure over time, disaggregating Seidl et al.’s data by country. Data reproduced with permission from Andrew Seidl. All values are normalised relative to 2010 for each country, *except for Canada whose baseline year in Seidl et al.’s dataset is 2015. A) Comparing biodiversity spending as a percentage of GDP for countries’ with official reported biodiversity expenditure statistics (all values converted into 2010 constant USD, so changes denote changes in real expenditure). B) Comparing UK spending as a percentage of GDP with countries reporting expenditure through the BIOFIN survey methodology. C) Comparing biodiversity spending as a percentage of the national budget for countries’ with official reported biodiversity expenditure statistics. D) Comparing UK spending as a percentage of the national budget with countries reporting expenditure through the BIOFIN survey methodology.

This internationally-leading decline in funding does not reflect a lack of need. According to Defra and the RSPB, the UK is on track to miss 14 to 17 of its 20 Aichi targets10,11, and it falls well behind on its 25 year Environment Plan policy commitments to restore 75% of protected sites to ‘favourable’ condition12 – current estimates suggest that this figure currently sits at 39% (for SSSIs)13.

Seidl et al.’s data is a valuable contribution to the empirical international biodiversity expenditure literature. There remains opportunities for future work, especially disaggregating between different budget lines at a national level in a standardised way14. Recent detailed national-scale budgetary analyses have demonstrated large mismatches between conservation need and expenditure15, which can help build robust evidence for setting the optimal levels of biodiversity expenditure nationally. Governments can greatly assist by publishing higher resolution disaggregated data.

The UK grew £250 billion per year wealthier in real terms from 2008-2018. Global environmental challenges are the most severe they have ever been. Rather than increasing their ambition in order to rise to these challenges, the UK government has chosen to shrink from them, even as Seidl et al.’s data suggests other countries’ ambition is rising, or at least constant in real terms. Seidl et al.’s new data demonstrates the stark divide between words and will; despite its supposed position of international leadership, the UK has in recent years deprioritised nature investments relative to other priorities, and is a global laggard in investing in the enhancement of the living world - a position that must be reversed if it to have any moral authority as leaders of this year’s COP26.

This article accompanies the following Correspondence in Nature. If citing this blog, please reference it as: zu Ermgassen, S.O.S.E., Bull, J.W., Groom, B. (2021) ‘UK biodiversity: close gap between reality and rhetoric’, Nature 595, 172.

References

- Defra. Environment Secretary to set out plans to restore nature and build back greener from the pandemic. GOV.UK https://www.gov.uk/government/news/environment-secretary-to-set-out-plans-to-restore-nature-and-build-back-greener-from-the-pandemic (2021).

- Office of the Prime Minister. PM commits to protect 30% of UK land in boost for biodiversity. GOV.UK https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-commits-to-protect-30-of-uk-land-in-boost-for-biodiversity (2020).

- Dasgupta, P. Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review. (2021).

- UK COP26. UK Climate Leadership. UN Climate Change Conference (COP26) at the SEC – Glasgow 2021 https://ukcop26.org/uk-presidency/uk-climate-leadership/ (2021).

- Office of the Prime Minister. The Queen’s Speech 2021. (2021).

- Seidl, A., Mulungu, K., Arlaud, M., van den Heuvel, O. & Riva, M. The effectiveness of national biodiversity investments to protect the wealth of nature. Nature Ecology & Evolution 5, 530–539 (2021).

- JNCC. UK Biodiversity Indicators 2020. Indicator E2 – Expenditure on UK and international biodiversity | JNCC

- RSPB. Biodiversity Loss: The UK’s Global Rank for Levels of Biodiversity Loss. https://www.rspb.org.uk/globalassets/downloads/about-us/48398rspb-biodivesity-intactness-index-summary-report-v4.pdf?fbclid=IwAR1re8NegdqeX7c5LsjqczUKJvrnwgb-aSxgds3CwRk8QDSmW7uK7SL5ty8 (2021).

- The Guardian. Natural England to get 47% funding increase amid ‘green recovery’ plans. http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/may/20/natural-england-to-get-47-funding-increase-amid-green-recovery-plans (2021).

- Defra. United Kingdom’s 6th National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity - UK Biodiversity Indicators. https://jncc.gov.uk/our-work/united-kingdom-s-6th-national-report-to-the-convention-on-biological-diversity/ (2020).

- RSPB. A lost decade for nature. http://ww2.rspb.org.uk/Images/A%20LOST%20DECADE%20FOR%20NATURE_tcm9-481563.pdf (2020).

- HM Government. 25 Year Environment Plan. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/693158/25-year-environment-plan.pdf (2018).

- Defra. Extent and Condition of Protected Areas. http://ex.ac.uk/cwP (2020).

- Groom, B. & Weinhold, D. M. New data on public biodiversity spending. Nature Ecology & Evolution 5, 409–410 (2021).

- Wintle, B. A. et al. Spending to save: What will it cost to halt Australia’s extinction crisis? Conservation Letters 12, e12682 (2019).