General information on meningitis and septicaemia for staff and students

Meningitis and septicaemia information

Meningitis is a very serious, potentially fatal infection. While cases are relatively rare, teenagers and young adults are a risk group, so need to be alert to signs and symptoms.

We have had cases at the University and so please read the information within these pages carefully.

Know the signs – you can find out more about the symptoms of meningitis below or on the NHS website.

Get help

If you think you may have meningitis seek medical advice immediately:

- your own doctor

- Call the NHS on 111

- the University Health Centre, Streatham Campus (Tel: 01392 676606)

- the Penryn Surgery on the Penryn campus (Tel: 01326 372502)

- for urgent medical support call 999

Viral meningitis is the most common type. Symptoms are usually mild (like the common cold) and recovery is normally complete without any specific treatment (antibiotics are ineffective). In most cases admission to hospital is unnecessary (although it is still notifiable to the Health Protection Agency).

Bacterial meningitis is a rare disease, but it can be very serious and requires urgent treatment with antibiotics. There are two main forms of bacterium: pneumococcal and meningococcal (of which there are five groups (strains) A, B, C, Y and W135).

Pneumococcal meningitis mainly affects infants and elderly people, but people with certain forms of chronic disease or immune deficiencies are also at increased risk. There is a vaccine available to protect people at high risk. It does not normally spread from person to person and public health action is therefore not usually needed. The pneumococcal bacterium is better known as a cause of pneumonia.

Meningococcal meningitis is the most dangerous type of bacterial infection. The bacterium can give rise to meningitis and/or septicaemia. Public health action is always required to identify cases and arrange preventive antibiotic treatment to close contacts of a case of meningococcal disease. Meningococcal disease is fatal in about one in ten cases.

Look at the Signs and Symptoms section for further information.

Septicaemia is a type of blood poisoning caused by bacterial meningitis. The bacteria release toxins which break down the walls of the blood vessels allowing blood to leak out under the skin and reduces the amount of blood available for vital organs. Septicaemia is often more life threatening than meningitis.

Meningitis

Meningitis is not easy to detect at first because the symptoms can be similar to those of flu. Recognising the symptoms early enough could mean the difference between life and death. The illness may take over one or two days to develop but it can develop very quickly with the patient becoming seriously ill in a few hours. If the patient’s condition deteriorates, do not delay … go straight to hospital, or call 999.

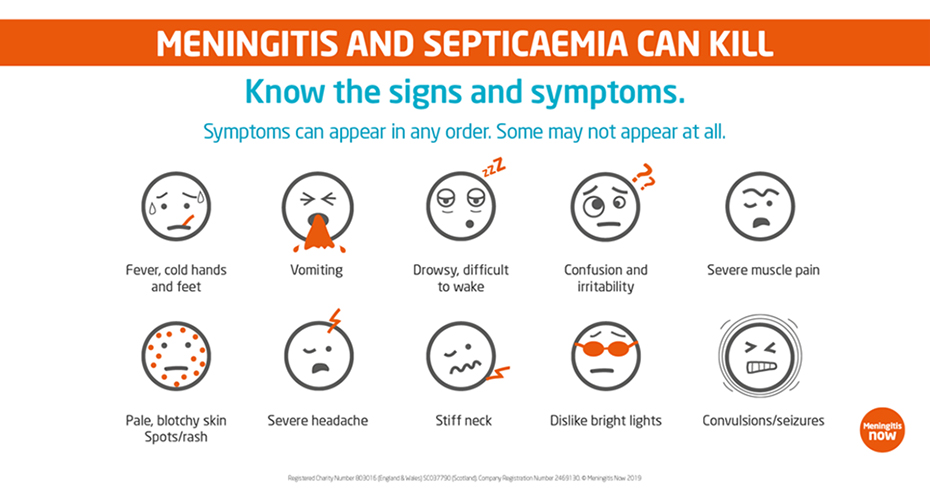

The following symptoms may not all appear at the same time:

| Symptom | Check for: |

|---|---|

| Fever/Vomiting (occasionally diarrhoea) |

|

| Headache |

|

| Stiff neck, aching limbs and joints |

|

| Dislike of bright lights |

|

| Drowsiness/Impaired Consciousness |

|

| Rash (haemorrhagic/septicaemic rash, not always present) |

|

| Seizures (fits) |

The early signs of septicaemia (blood poisoning) include:

- Fever with cold hands and feet

- Severe muscle pain

- Pale, blotchy skin

- Stomach cramps diarrhoea

Septicaemia can progress very quickly, resulting in severe shock, and in some cases, death within hours. If septicaemia is suspected, urgent medical help is needed. Call 999 for an ambulance or go to your hospital's A&E department.

If a student or member of staff has meningitis, we work with the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) following their guidance, to support the person concerned. We also enable the identification of any other students or staff who may be at risk, so that they can be contacted and if appropriate, offered antibiotic treatment.

Meningococcal bacteria are carried at the back of the throat or nose by up to 10% of the general population (and up to 20% of young people). Only rarely does infection (or colonisation) give rise to disease. Illness usually occurs within seven days of acquiring the bacteria, but symptom-less carriage can persist for many months. It is not known why some people become ill and others remain healthy carriers. The bacteria do not survive for long outside the body and most people acquire infection from prolonged, close contact with a symptom-less carrier. Infection is usually acquired from a healthy carrier rather than from a person with the disease.

Most cases of meningococcal disease are sporadic. However, the risk of a second case in a close household contact is much higher than the risk in the general population. In spite of this, clusters of disease are uncommon, occurring only occasionally in households and rarely in places such as higher education.

The NHS and University strongly recommend that all students make sure they have had the MenACWY vaccine, which offers protection against four strains of the meningococcal bacteria, which can lead to meningitis. The vaccine is offered FREE to people aged under 25 in the UK.

In the UK this is routinely offered to children in school, but your doctor will be able to confirm whether or not you have received it.

If you haven't received it, or are an international student who has not been offered it in your home country, do get in touch with the Student Health Centre (for students in Devon), Penryn Surgery (students in Cornwall) or your own doctor (if different) and book an appointment. You can read more about the vaccine here.

Antibiotics: Preventive treatment with oral antibiotics are recommended for close contacts of a case of meningococcal disease in order to reduce the risk of further spread of infection. Close contacts are contacted by UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) once a case has been identifed. As the infection does not easily spread from person to person there is generally no need for wide-scale preventive measures.

Vaccination: The NHS and University strongly recommend that all students make sure they have had the MenACWY vaccine, which offers protection against four strains of the meningococcal bacteria, which can lead to meningitis. The vaccine is offered FREE to people aged under 25 in the UK.

In the UK this is routinely offered to children in school, but your doctor will be able to confirm whether or not you have received it.

If you haven't received it, or are an international student who has not been offered it in your home country, do get in touch with the Student Health Centre (for students in Devon), Penryn Surgery (students in Cornwall) or your own doctor (if different) and book an appointment. You can read more about the vaccine here.

If you think you may have meningitis seek medical advice immediately:

- your own doctor

- Call the NHS on 111

- the University Health Centre, Streatham Campus (Tel: 01392 676606)

- the Penryn Surgery on the Penryn campus (Tel: 01326 372502)

- for urgent medical support call 999

Further general information about meningitis:

- Meningitis Now (0808 8010388)

- the Meningitis Research Foundation (0808 8003344)

- the NHS website