Development Fund 2022/23: Does Increasing Public Spending in Health Improve Health?

Damian Clarke (Economics, ESE): Does Increasing Public Spending in Health Improve Health? Lessons from a Constitutional Reform in Brazil (with Rudi Rocha and Michel Szklo)

Overview:

This project seeks to estimate the causal impacts of public health spending on individual health outcomes in Brazil. It studies a major health reform in Brazil in which municipalities were mandated to spend 15% of their revenue on health. Collecting microdata covering 5,507 Brazilian municipalities over 12 years, this project finds that the large increases in spending resulted in increased availability of hospitals and health professionals, greater individual access to primary care, and improvements in certain health outcomes such as infant mortality, with less evidence suggesting improvements in adult mortality.

On Wednesday 17th April 24, Damian Clarke will be discussing this project as part of SCI's Project Showcase Series. To find out more about the event, and to register, please click here.

Read on to learn more about the project and its findings...

Understanding the Dynamics of Healthcare Spending and its Effects: Evidence from a Constitutional Spending Reform and Health Outcomes in Brazil

Damian Clarke, Rudi Rocha and Michel Szklo

Global healthcare spending has more than doubled in real terms since the turn of the century, reaching US$ 8.5 trillion in 2019, or 9.8% of global GDP, and it is estimated to reach over US$24 trillion by 2040. Most of this growth has been funded by public sources. Half a century ago, government health expenditure as a share of GDP was not higher than 3% in OECD countries, and now ranges between 7% and 10% in most cases. Yet, there is surprisingly scarce causal evidence on whether government health expenditure is effective in improving health outcomes. Evidence is particularly sparse in developing countries, where life expectancy is generally lower and unmet social demands are greater.

This may seem surprising given the major role that health care spending plays in national budgets, and the pressing social needs in other areas which calls for an understanding of where (limited) public resources should best be directed. However, one reason why evidence is scarce is that credibly estimating the impact of health spending on health outcomes is difficult. In general governments seek to direct health care resources to the places where they are most required. This can conceivably result in patterns in real world data in which areas with the poorest health outcomes have the greatest need for resources and hence the highest health spending, implying challenges in isolating causal effects. This suggests the importance of finding some variation in spending shifts which is not related to population-level health outcomes. Finding such variation in a setting as complex as government health spending is not trivial, which has limited the scope of research in this regard.

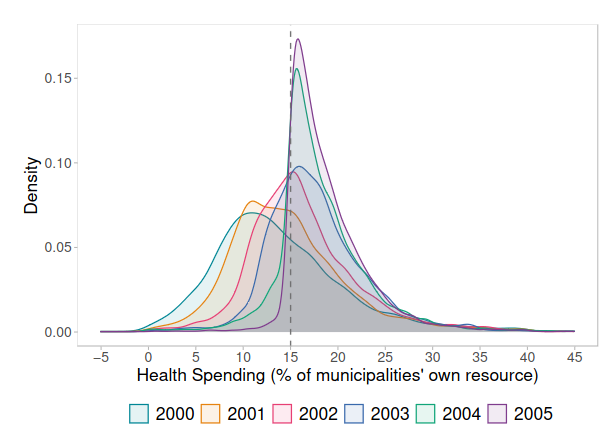

It turns out that a major reform to Brazil's healthcare system provides a compelling case study to understand this phenomenon. In 2000, the Brazilian government enacted the 29th Constitutional Amendment, ushering in a new era of public health spending. This landmark amendment mandated a minimum allocation of resources from federal, state, and municipal governments towards healthcare services, thereby injecting a substantial influx of funds into the country's healthcare system. What is of particular importance for understanding the impact of health spending on population health is that this reform set mandatory minimum spending floors. In particular, it mandated that each municipality in the country must spend at least 15% of all of its revenue on health care. This resulted in a situation in which municipalities spending below 15% of their budget on health at baseline quickly had large increases in health spending to meet the mandate, while areas which spent around 15% of their budget or more did not increase health spending, or even reduced spending in line with the 15% target. This can be observed in the figure below. Municipalities were given 5 years to meet the spending thresholds imposed in the year 2000, and were required to move towards the target each year. For this reason, we observe that by 2000, spending in health had sharply increased, nearly and at the lower end bunched very close to the 15% spending target.

New research which we have conducted shows the complex results of this spending reform as it propagated through the entire public health system, and beyond. We collected a large range of measures: from initial inputs such as spending figures, investments such as hospital construction and staff coverage, health care access measured by the coverage of key public programs and rates of inpatient treatments, as well as final outputs such as mortality. Our study, which covers virtually all of Brazil’s 5,570 municipalities from 1998-2010, uses this “natural experiment” driven by the spending reform to examine the multifaceted impacts of health spending reform across the country.

Our findings suggest that marginal increases in health spending generate noteworthy impacts on health inputs and outcomes. In areas which most increased spending, infant mortality rates fell more than in areas which did not increase spending. These mortality effects are driven by increases in municipal hospital construction and access to health care professionals, with access to primary care and community care being particularly important levers. While the link between health spending and health outcomes may seem, prima facie, unsurprising, many things must go right for health spending to impact final health outcomes. Among other things, concerns may exist that spending is diverted into

corruption or patronage, or spent in ways that do not actually track through into improved health outcomes. Our results suggest that in the context studied, spending has affected health inputs in a way which has increased access to the health system, and also resulted in measurable improvements in infant health. Our results do not, of course, suggest that public spending is a panacea for improvements in all forms of health outcomes. We observe that impacts of spending are most relevant when considering outcomes such as infant health amenable to primary care (e.g. reducing mortality related to perinatal and infectious causes that can be averted upon access to primary care services), with less obvious effects observed when considering adult mortality, which is often related to chronic causes.

Nevertheless, overall, our results suggest that while health care spending increased by around 10 billion USD per year, at a national level the reform resulted in 2,500 fewer infant deaths per year. Aggregated over the entire time frame of our study, our results suggest that for each (approximately) $750,000 USD invested, an infant death was averted, which is an impressive record suggesting public value in health spending. As policymakers worldwide grapple with the daunting task of reforming healthcare systems and improving health outcomes potentially in periods of budget restrictions, studies such as these serve as invaluable guideposts, offering evidence that – especially in low-income settings – health spending has substantive return, mapping directly into certain fundamental tenets of social wellbeing.